During the 1960’s Alexander Shulgin gave MDMA to a psychologist friend, who thought it could have myriad applications in psychology (the friend, Leo Zeff, had been preparing to retire, but after trying MDMA, he decided not to). Slowly, over the next several years, a network of shrinks developed—about 4,000 of them—who used the drug regularly in their practices. They found it incredibly effective in removing emotional barriers; one called it “penicillin for the soul.” Some used it in marriage counseling sessions, others to treat post-traumatic stress disorder.

The spread of MDMA in clinical settings went completely unnoticed by law enforcement until 1984. Of course, some had leaked out onto the streets, and it was in limited circulation as a party drug; that’s how it fell into the hands of seminary student Michael Clegg in the late ’70s, who says taking it was like “hearing Moses on the mountain.” Anxious for others to share the experience, he began giving it to friends, then selling it to cover his costs, then selling it for profit. But MDMA seemed too clinical, so he came up with a brand name: ecstasy. By this time, Clegg was a full-on Catholic priest.

By 1984, Clegg was moving tons of the drug to local nightclubs and had even set up a mail-order service with a toll-free number; his business had made him a millionaire. Of course, this finally made authorities sit up and take notice. By the following year, MDMA was illegal and classified as a Schedule 1 narcotic. By definition, this means it has no medicinal or therapeutic value—but tell that to the many patients whose lives it changed before its outlawing. It should, of course, be noted that these patients took it under supervision and that any drug can be incredibly harmful if used irresponsibly.

Clegg claims to have tried MDMA for the first time in 1978 or 1979, when he was forty years old. “My eyes opened up in a way I never imagined possible on the earth,” Clegg later recalled of that first experience. But he’d need assistance in seeing that vision through. In 1983 a knock came to the door of a Mendocino County, California, resident named Bob McMillen. McMillen had “a bit of a reputation” in the area, as he explained to me. For one, he lived in a castle overlooking the ocean. He had also formerly run a major marijuana smuggling and distribution ring that brought billions of dollars’ worth of weed into the United States, first from Mexico and then from Thailand.

The man at McMillen’s door was Clegg. He told McMillen he’d moved to Mendocino three months earlier. He’d heard of Bob, and he was here to pitch him on a new drug he called Therapy. McMillen was immediately repulsed. He was hooked on cocaine at the time, and the last thing he needed, he told Clegg, was another drug. But Clegg kept pushing. He even claimed that Therapy could sever McMillen’s relationship with coke. McMillen rolled his eyes and shooed Clegg off his property. But he did accept some reading material Clegg gave him about the drug.

Eventually McMillen wound up agreeing to Clegg’s offer, partly because he seemed so sincere—and also because he just wouldn’t leave McMillen alone. Clegg and his wife, Pauline, arrived at five o’clock one evening in a white BMW. The couple put on a new Deuter album called Ecstasy and draped a blanket over McMillen, who lay on the couch. “I was extremely dubious,” he said. “I didn’t take pills.”

After about twenty minutes, McMillen felt a chill. Suddenly the music “lit up like nothing I’d imagined,” he recalled. “I floated off in a wonderful euphoria for a while, then I threw the sheet off, sat up and said, ‘Sold! How much can I get?’ ”

McMillen agreed to help put the new drug out on the street. “We sold billions of dollars of pot, so I already had the infrastructure,” he said. But the first order of business, he insisted, was changing the drug’s name. “‘Therapy’ will never sell,” he told Clegg. He suggested Ecstasy, after the Deuter album. Clegg at first pooh-poohed the idea: he’d already printed labels for bottles of Therapy. But when McMillen sold five thousand pills in four days under the name Ecstasy, Clegg came around. So much so, in fact, that he would later claim that he was the one who came up with the name Ecstasy.

As he told Playboy, “It came to me: It was pure ecstasy.” (When I told McMillen about Clegg trying to take credit for the name, McMillen just started laughing; when I asked Clegg about McMillen coming up with the name, Clegg insisted that he’d called it Ecstasy from the beginning, adding, “Bob McMillen was the biggest liar I ever knew.”)

For a short time Clegg linked up with the Boston Group as their Southwest distributor. But he wasn’t happy with how the Boston chemists were prone to falling off the radar, or how they wouldn’t supply him with the massive quantities of MDMA that he wanted to sell. After he got his hands on the drug’s chemical formula (he claimed to various people to have been given it or to have bought it; in fact, it was published in the scientific literature), he found his own chemists to produce the drug in California. Within weeks McMillen had distributed MDMA “coast to coast,” he said. “This took off like an explosion.”

“This took off like an explosion.”

— Michael Clegg

McMillen set up a beeper with the number 1-800-ECSTASY for taking orders, and within a couple of months, he said, demand had soared to a hundred thousand pills per week. McMillen’s guy in Hollywood distributed it among movie stars. Others passed it out to people in the music industry, who “just gobbled it up,” McMillen said. “I got one testimonial after another, people were just unbelievably happy.”

Despite the hiccups, Clegg’s Ecstasy business grew to around twenty-five people. He started referring to them as the Texas Group, since his main partners were from there, and Dallas was becoming a major hub.

Although Ecstasy was still legal, McMillen knew enough about the government’s zero-tolerance approach to drugs to urge his associates to proceed with caution. (One member of the crew would regularly fly to Texas with a bag of twenty thousand Ecstasy pills marked “Rabbit Food.”)

Discretion was not Clegg’s strong suit, however. He and Pauline spread MDMA throughout the Dallas community by throwing Tupperware-style “XTC” parties at their Dallas condo and in lavish hotel suites. Guests would listen to a lecture about MDMA and be given a 100- to 125-milligram dose.

Based on his guests’ tendencies to want to dance while high, Clegg struck on another brilliant idea: introduce MDMA to the clubs. As Torsten Passie said, “He brought it to the discotheque, and then it became great.” Michael recruited distributors to hand out brochures advertising the new drug at the Starck Club and other venues.

It wasn’t just customers whose eye Clegg caught, though. The police began getting complaints about “this hippy-type atmosphere that existed with the introduction of Ecstasy into the Dallas metroplex,” Phil Jordan, the director of drug intelligence at the DEA at the time, told Cain in an unpublished interview. Ecstasy also came to the attention of then U.S. senator from Texas Lloyd Bentsen. The Democratic congressman contacted the DEA in 1985, urging them to schedule MDMA and put a stop to what he saw as a growing epidemic.

The DEA’s Texas office was primarily focused on methamphetamine, cocaine, and heroin. But when officers began looking into “that kiddie drug,” as some agents called Ecstasy, they realized that Dallas had become a major hub.

In recent years, growing numbers of scientists have been asking whether MDMA could become a recognized, official part of psychotherapy. Rachel Yehuda, who runs a lab at Mount Sinai focussed on post-traumatic stress disorder, or P.T.S.D., says that MDMA “produces a substantial change in mental state that increases people’s ability to engage with traumatic material in psychotherapy.” Although the drug has been illegal since the eighties, the F.D.A. considers MDMA one component of a “breakthrough therapy” for the treatment of P.T.S.D., and could soon consider an application for its prescription use during therapy sessions. Such a development would force us to change our idea of the drug. Many people still think of MDMA as a chemical that makes you feel good when you go out dancing all night long. But what if its greatest power is an ability to inspire empathetic conversations? The meaning of MDMA is changing. What kind of a drug is it going to be?

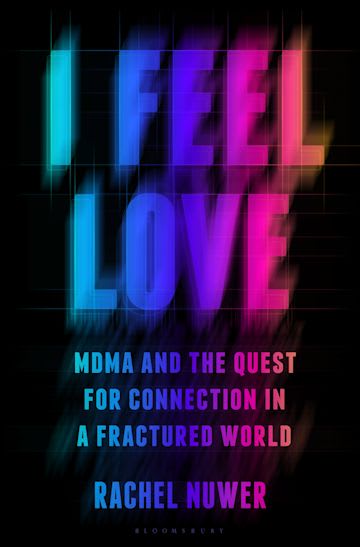

MDMA takes its name from its chemical formula: 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. In “I Feel Love: MDMA and the Quest for Connection in a Fractured World,” a new book on the history and resurgence of the drug, the journalist Rachel Nuwer writes that it was first synthesized in the U.S. in 1965, by Alexander Shulgin, a gifted chemist at Dow Chemical. Shulgin, who taught at the University of California, Berkeley, and consulted for the Drug Enforcement Administration (D.E.A.), was part of a community of psychedelic enthusiasts who “tended to think of MDMA as a cherished and respected medicine,” Nuwer writes—“something to assist with transcendence, growth, and healing.” The drug became popular among therapists of a countercultural bent, who administered it to patients and sometimes took it themselves. But, as others began to synthesize and share it, Shulgin feared that it would become known as a recreational drug and the D.E.A. would criminalize it.

MDMA’s reach grew in the early eighties, when a former Catholic priest named Michael Clegg introduced it to the Dallas club scene. It proved successful enough there that, one day, he visited Bob McMillen, who had been a major marijuana distributor in California. He told McMillen that he had been using a drug that was going to be a big deal, and he wanted to sell it on the West Coast. Clegg even had a name for the molecule: Therapy. After some cajoling, McMillen agreed to sample it. He put on an album by the New Age instrumentalist Deuter and sat on his couch, under a sheet. “I floated off in a wonderful euphoria,” he later recalled. “Then I threw the sheet off, sat up and said, ‘Sold! How much can I get?’ ” But McMillen insisted on a rebrand: Therapy was too corny a name to move any product. He chose the name of the Deuter album, and in four days he sold five thousand units of Ecstasy.

MDMA was gaining a sort of split personality, as a potentially therapeutic chemical on the one hand and as pleasure in pill form on the other. Shulgin hated the name Ecstasy; when Nuwer visited his widow, she called it “penicillin for the soul.” On the party scene, however, it was becoming commonplace for clubbers to go to a bartender and order “a beer and an Ecstasy,” one of Nuwer’s sources recalls. Users didn’t necessarily know what they were getting: Ecstasy is often cut with other drugs, such as fentanyl. In part for this reason, in 1985, the D.E.A. named MDMA a Schedule 1 controlled substance—a classification reserved for drugs “with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.”

In the decades that followed, a research and advocacy organization, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, or maps, tried to make psychedelics acceptable and accessible to the public. But not until the two-thousands did studies of MDMA’s therapeutic potential start to gain wider traction. In a Phase 2 clinical trial started in 2004, a hundred and seven people with a P.T.S.D. diagnosis received several weeks of talk therapy; during two of the sessions, about a month apart, participants received either MDMA or a placebo. When the study concluded, fifty-six per cent of those given MDMA and therapy no longer met the diagnostic criteria for the disorder, more than twice as many as those in the placebo group. One downside of such studies is their small size; another is that they do not test MDMA without therapy, making it difficult to disentangle the impacts of the drug from the sessions.

Nuwer argues that the effort to recontextualize MDMA as a treatment for trauma is both “the latest installment in a long history of hype that’s surrounded this unique molecule” and a return to the drug’s roots. “The pendulum is swinging back to where MDMA began,” she writes. Recently, an Australian law made MDMA and psilocybin, the compound in psychedelic mushrooms, available by prescription; an Australian biotech company raised $2.5 million to develop a program for psychiatrists to provide MDMA during therapy. In 2021, a psychiatrist associated with maps, Michael Mithoefer, published a Phase 3 trial—the first late-stage clinical trial involving MDMA—with promising results for patients with severe P.T.S.D. Now that Mithoefer and his colleagues have completed an additional Phase 3 trial, his team plans to submit an application for prescription use to the F.D.A. Nuwer writes that some psychiatrists are skeptical about whether the drug is ready for “widespread clinical use,” but many experts think that it could be approved as soon as this year.

We’re used to thinking of psychiatric medications as working separately from therapy, with the former making physiological changes to brain chemistry and the latter helping patients understand their emotions, adjust their thinking patterns, or change behavior. But MDMA doesn’t fit that model of psychiatric medication; it’s fundamentally different from the drugs that currently treat depression or anxiety. No one is suggesting that patients take MDMA every day, like Wellbutrin, or as needed to combat acute distress, like Xanax. Instead, MDMA is a drug that one might take in combination with therapy, during sessions—less a treatment than a treatment enhancer.

The exact mechanisms through which MDMA works are not well understood. During the last four decades, most research on the drug has focussed on whether it damages the brain; studies are ongoing, and Nuwer’s expert sources are convinced that it doesn’t—although, she writes, it is clear that “high, repeated doses can inflict major changes” on the serotonin systems of lab animals. One of Nuwer’s important contributions is dissecting two seriously flawed studies of MDMA that have been corrected in the scientific literature but have nonetheless shaped public opinion. In one, researchers mistakenly administered methamphetamine to subjects, yet reported the results as coming from MDMA.

Gül Dölen, a researcher at Johns Hopkins, has found that MDMA and other psychedelics reopen what neuroscientists call a “critical period” in the brain—windows of time, mostly occurring during childhood and puberty, during which neural connections can change and reorganize. It’s unknown whether this has anything to do with the feelings of empathy and social connection associated with the drug. Dölen points out that individuals receiving MDMA-assisted therapy need to be treated with particular care, not just during their sessions but afterward; even after the drug’s acute effects have worn off, patients will “continue to exhibit heightened sensitivity, malleability and vulnerability during the open state.” (One woman who had participated in a maps-sponsored trial, in Canada, continued treatment with two therapists who had conducted the trial; she later accused one of them of sexual assault during sessions. He claimed in legal filings that the relationship was consensual; maps cut ties with both therapists.)

If the F.D.A. approves MDMA for use during therapy, this will represent an unprecedented development both for psychedelic drugs and for therapy. A substance that has long been associated with parties could be mainstreamed and medicalized; many more people might try a new category of mental-health care, which could come with new kinds of risks. There could come a day when MDMA is associated less with feeling good than with trying to get better. As patients in Mithoefer’s studies have told him, “I don’t know why they call this Ecstasy.”

In the late nineteen-nineties, a psychiatrist named Charles Grob published a study showing that MDMA could be safely administered in a medical setting. His researchers administered the drug at a hospital to volunteers who, per the F.D.A.’s requirements, had prior experience taking it. The only person who had a problem with the tests, he reported, was the head nurse. She was annoyed that her nurses were neglecting their duties, instead choosing to spend time with the study participants. “The subjects were so empathetic and interested in the lives of the nurses,” Grob wrote, that the nurses gravitated to them, eager to talk. One of the peculiarities of MDMA is that it turns its users into listeners. Back in college, during our “session” with John, it was our MDMA-heightened empathy that helped the conversation along. John didn’t need to take drugs to benefit from its effects; he just walked into the room.

Nuwer writes that, when she tried MDMA for the first time, at a warehouse party in Brooklyn, she was worried that the drug would cause her to “spontaneously start making out with everyone.” But the sexiness associated with MDMA might not be one of its intrinsic properties; instead, the drug might work more broadly to deepen our interest in others. Therapy is a social pursuit: a good therapist provides not just insight and tools but a relationship in which it’s possible to change. When someone takes MDMA in the presence of a therapist, they might feel more supported and secure in this bond, and more able to dredge up painful feelings or hard memories without being overwhelmed by fear or shame. When I took it, I felt my bond with John a little more powerfully.

It could be that MDMA simply intensifies something that’s already present in successful therapy. Therapy helps, in part, because human connection is good for us. It matters when someone listens to you, and when you listen. Recently, I reached out to John to ask him how he recalled our encounter in the dorm bathroom. On the phone, our old rapport quickly reëstablished itself; the longer we talked, the better I felt. When I asked about that day, he laughed and told me that he remembered our conversation as a soothing one. But he never suspected that we were on MDMA. “You guys were my friends,” he recalled. “I knew you were empathetic people.” That had been enough. ♦